Sculpture Center, New York, 1992

SONIA BALASSANIAN:

THE OTHER SIDE

By Geoffrey Young

What happens when the primacy of eyesight, our central sense for interpreting the world around us, is denied? Vision has always been the critical factor in making sense of reality’s shifting images. To hove sight suddenly neutralized is disorienting. It affects mind and body equally. We’re forced to tune in to our environment via other senses, entertain other voices, read the scene with our bodies, slow down. Sonia Balassanian’s lighting in “The Other Side” is the crucial catalyst of our experience of her sculpture. Entering a room through a narrow door in a wall, our everyday relations with art and life are made strange as we are stuck by the light from on array of standing lamps. Like sentinels, or guardsmen, unadorned and spectral, the light from these lamps seems to pin our wings to the wall, stripping us of the very sense we trust most. But this light that strikes us, also strikes whatever else is in the room. Eventually, we can make out a semi-circle of dark seated figures, eleven of them in fact, draped in black cloth, situated just in front of the lamps, as elegant, as mute, as inscrutable as sphinxes.

Everything we know about physiognomy and the garb of different cultures tells us that these veiled presences ore women. What is their role in this dark site? Draped from head to toe in black cloth, we can determine only some minute variation in the folds of their drapery, their upright posture, their “boniness,” their immobility. Oppressed by the light in our eyes we wonder: are these silent souls sitting in judgement, do they have the power to interrogate or condemn us? We have walked, unwittingly, into the place where the powerless look for mercy from the inquisitorial authorities. Not only can’t we see these seated figures very well, we can’t “see” what they want from us. How sinister is it? What would these figures likely say if they spoke? How are we related to them, we who parade our faces as unquestioned badges of our identities? What would happen if these seated figures suddenly stood up, threw off their veils and walked away? How far would they get? What is holding them back? To what dark forces have they succumbed? This is no Allegory of the Cave, though it is about ideas. Rather we are being set into the dynamic of complete repression. The discomfort is palpable in this stark and confrontational space. How do we feel? Though some viewers might rationalize: “This could never happen to me, I’ve got a cab waiting for me outside,” most of us will submit in the context of art to Balassanian’s shock theatre, undergoing sudden flashes of empathy for the cold sweat and the anger and fear that any victim feels before the harsh light of authority.

But remember: every threat to our autonomy is also the chance to show courage, resistance. Though neither our own individuality nor the oppressor’s conformity is the issue, commiseration with the plight of the dispossessed and politics of liberation are. “The Other Side” is like an inoculation which prepares us for a worst-case scenario in the world.

Balassanian’s seated figures, which over the last two years she has cobbled together from disparate found elements, number eleven. Though the numbers don’t match up precisely, nor do the narratives, they call to mind the robed figures of our own Supreme Court in all their stiff formality. Judges have the power to decide the constitutionality of laws as well as the criminality of individual cases, and thereby affect us all. But Balassanian’s figures belong more properly to some nether rung of Dante’s hell. That we may never know their true identity is perhaps the point. Whether they have capitulated to the forces of oppression and are themselves part of the regime, or whether their presence in this theatre of anxiety challenges us to think about our own relation to power and authority, the uncertainty and ambiguity are intended. She has kept the terms of her tableau dramatically so as to admit of various readings. For her, it is not enough to show horrible events. The only way to get our attention now is to simulate the conditions whereby we might come to experience the loss of freedom, begin to feel for, and if only for an instant even, suffer the nightmare of the victim. Only empathy, she seems to be saying, will ignite human response. By instinct as well as conviction, Balassanian knows every nuance of the English poet John Donne’s celebrated “No man is on island” lines: “Any man’s death diminishes me, for I am involved in mankind.”

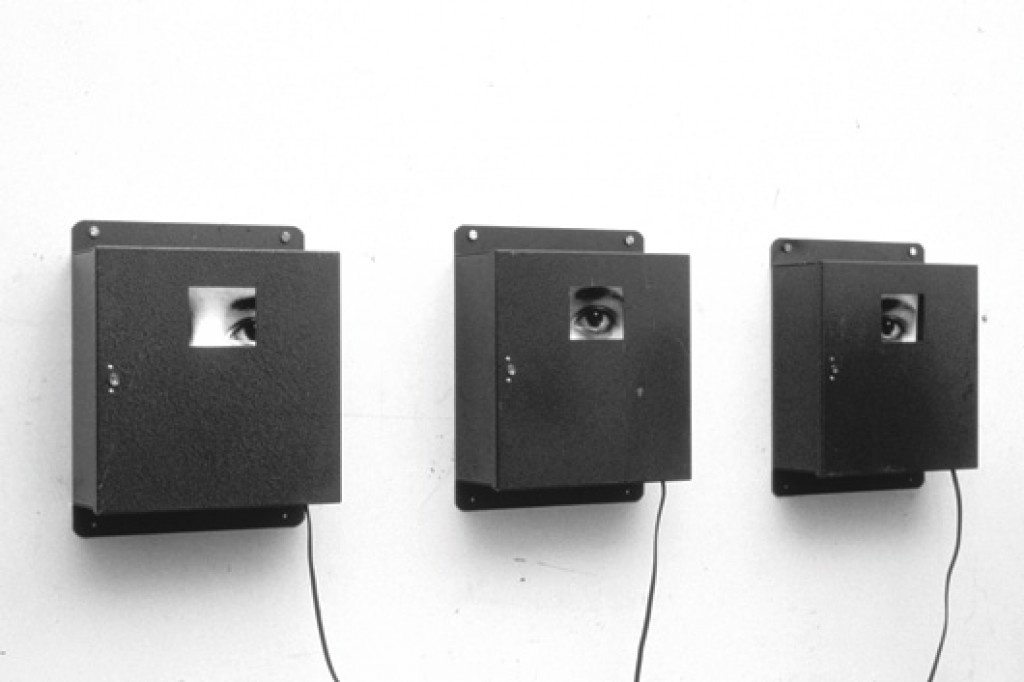

In the smaller back room at the Sculpture Center, she has installed a dozen or so fuse boxes at eye level. Inside each box there are two objects. One, a bulb, lit but out of sight, and the other, a close up photograph of a young woman’s beautiful dark eyes. She gazes out at us through a 3″ x 3W’ rectangular hole in the lace of each box. No other light source has been added to the piece. Walking by these boxes, we notice that her eyes seem to follow us. Suddenly we feel that this young woman is the observer, that we are the observed. Just as we felt stared of in the previous, larger room, by the faceless judgment light of authority, now we can’t escape the sustained scrutiny of her eyes. Who is she? What narrative is she the “I” of? Is she trapped within the box? What can we do?

Balassanian is not unaware of minimalist precedents for her kind of industrially produced repetitive objects, but her use of the fuse box is not literal, it’s poetic. She wants those eyes, that face, that person, and that culture set free from the shrouds, the cultural shackles and currents that delimit it. And she wants the viewer to be reminded of the difference.

At the level Sonia Balassanian is working, which is that of universal structure, does anything, it may be sad to ask, ever change? “Man’s inhumanity to man” seems a constant, forever and without end. A New World Order is just another bandaid phrase, while the scary truth is the constancy of cruelty. But art can focus feelings that make a difference. When we can admit that we too are the faceless, the innumerable, the “disappeared,” the soon-to-be erased from history as well as the agents of that erasure, then some kind of reasonable ritual cleansing is in process. For terror can be domestic, it can be in the workplace, it is on the streets. But it is always here. Balassanian sets off an emphatic reaction, and like a shaman, would extract our sickness from us; in her carefully simulated doses she offers us o homeopathic cure. The kind of identity-suffocating repression that foreigners, ethnic minorities and women are subject to in this country can find their champion in Balassanian, for as a woman born and raised in a foreign culture, she knows firsthand what slights and invisibilities the outsider feels in this deeply competitive socially networked, racially stratified society.

As we open the door into “The Other Side” we are submitting to an experience. Only the viewer, one by one, can say what impact or seed of sensitivity was sown in that moment of disorientation and vulnerability.

Extract from the Exhibition Catalog,

Sculpture Center, New York, 1992